Wellville is an unusual outfit. Yes, we have a formal structure – a 501c3 nonprofit – but our goal is not to self-perpetuate or to scale. Rather, our goal is to leave politely, with everything in the hands of community members themselves, by the end of 2024. One of our core tenets is that in the long run, our communities need sustainable funding and support to decide for themselves what and how to improve their health and wellbeing, not unpredictable outsiders like us.

Wellville has contracts with our own team members, but not with the communities or organizations we work with. We don’t hand out money, nor do we charge for our questions and moral support. (We are not a parent who pays your college fees, but more a benevolent aunt who has your back. Precisely because she’s not paying for anything anyway, you can tell your aunt the full truth.) All along, since 2014, the National Wellville team has not done the real work; community members do. They own the resources and make the decisions. Most importantly, they own the results. We coach our communities as they do the work for themselves, not to please us or to fulfill the requirements of a grant.

Certainly we do some work: introducing community members to one another or to outside resources, organizing and running meetings, helping to prepare grant proposals and the like. The community members we work with can ignore us – and some have, over time! Others have come to value our support, our questions and our (mostly) gentle prodding.

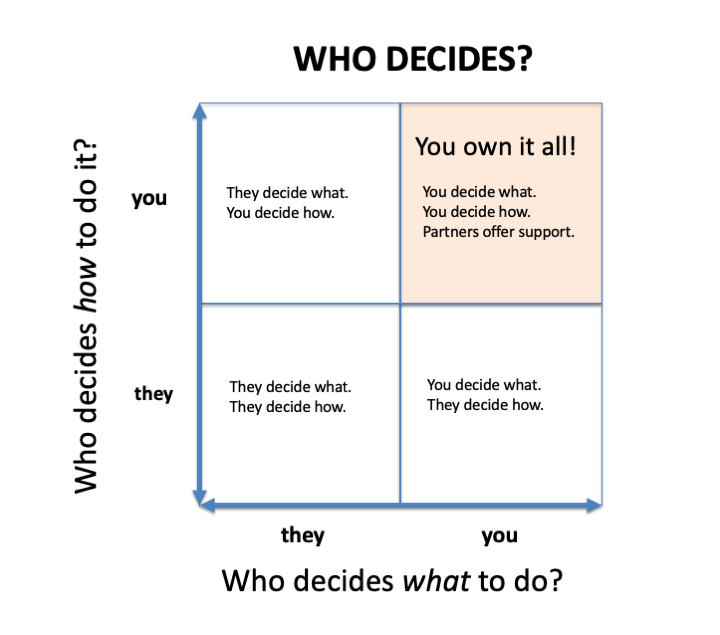

Perhaps the best way to explain our unusual role/methods is in a quadrant chart. Let’s call it the “Who decides?” chart. The chart visualizes how help is offered to communities by outsiders, including Wellville, who either tell you or ask you what to do or how to do it – or both! The “you” is the community members, in all their glory and variety of needs and capacities.

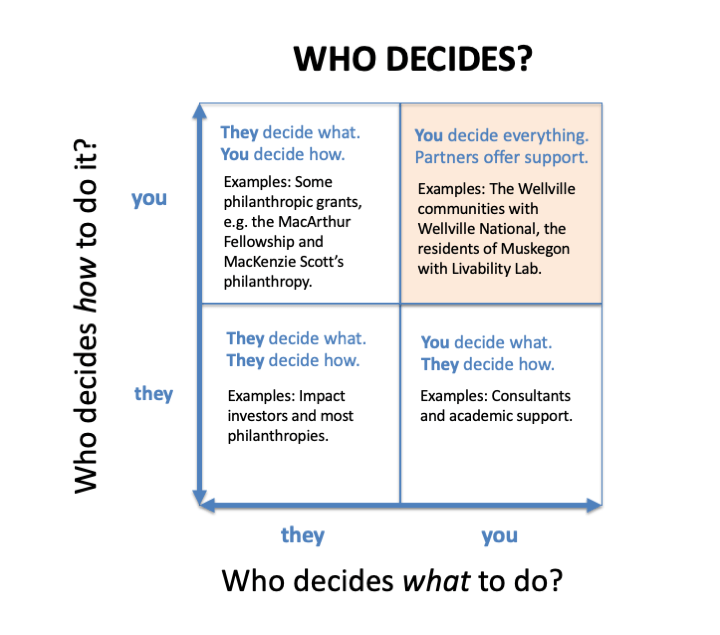

LOWER LEFT: THEY DECIDE EVERYTHING

Though there may be some collaboration, in the lower left quadrant someone else (“they”) decides both what and how. Ultimately, the outsiders who do this own the results. There’s not much left for the community except to receive the “gift” – whether they wanted it or not – and, usually, to pay the absentee landlords some kind of rent over time.

These outsiders can be “impact” investors who come in, usually with great promises of “improvements” as they define them, but without checking what the community wants. The outsiders may do a bit of hiring locally, but mostly they are gentrifiers, sending in their own people, “fixing things up” – and often driving out people who can no longer afford to live in their own communities.

Or these outsiders can be philanthropies that pit local organizations against one another to compete for short-term grants, forcing the would-be grantees to spend scarce money applying for projects they don’t really believe in… These grantmakers have their own ideas of what the community needs, and strict requirements for how you carry out their wishes. But that’s what will get the funding for the local organizations to keep their doors open for one more year. (If you’re reading this and think this describes you/your donor organization, maybe it does.) The outsiders tell the locals what the community needs, and how to achieve it… but they don’t create (a sense of) community ownership. The grant recipients are accountable to the funders, not to the supposed beneficiaries.

UPPER LEFT: THEY DECIDE WHAT AND TRUST YOU ON HOW

These are a few philanthropies that fund community projects without sending in troops to “help.” They can be very valuable when their interests align with the community’s. For better or worse, community organizations are awarded the funding and then pretty much left alone to do the work. Yet usually, these are short-term grants and ongoing funding is uncertain. Still, the world needs more of such unrestricted grantmaking. MacKenzie Scott’s arm’s-length philanthropy is one shining success. She picks her grantees based on what they are doing, and trusts them to determine how to carry the work forward. Another famous example, although given to individuals rather than community organizations, is the MacArthur Fellowship grant. It is given for what the individual has already done, with the faith that, to quote the website, “…highly motivated, self-directed, and talented people are in the best position to decide how to allocate their time and resources.”

This quadrant also includes unfunded government mandates, where policymakers tell you what to do without inquiring about how – or how to pay for it!

LOWER RIGHT: YOU DECIDE WHAT; THEY TELL YOU HOW

Now we’re getting somewhere! The community decides what it wants, and selects a vendor/consultant – or with luck, finds a university willing to fund and provide tech support – for the project. Usually there’s some two-way interaction about what to do… but there’s often a fairly rigid protocol and perhaps some fees associated with this communication and consultation. Projects may have a hard time sustaining themselves over time, as they depend on outside management.

But in the best cases, this type of work moves up the chart, into the upper-right quadrant. The outsiders pass on their learning and leave sustainable organizations and practices with the rightful owners – the community, which ends up with a magnificent, sustainable success.

Take Muskegon County, Michigan’s Livability Lab, originally an initiative of the federally funded, state-allocated Muskegon Community Health Innovation Region (CHIR, originally backboned by Mercy/Trinity Health’s Health Project, and later transferred to Access Health). The CHIR contracted with Michigan State University for its help in adopting the university’s ABLe Change project design and implementation process. In Muskegon this initiative came to be called Livability Lab. The first Livability Lab 100-Day Challenge (the culmination of some intensive planning with MSU’s guidance) launched on September 10, 2019. A bit more than 100 days later, on January 23, 2020, the first cohort of projects celebrated its achievements at a community gathering/reunion. Since then, the Lab has brought most of its operations and training in-community.

In other words, the Lab has moved from the lower-right to the upper-right quadrant on the chart. The former MSU trainees have become the trainers, and more community members have joined in, coaching newer members as peers. Importantly, the Lab is structured explicitly so that local residents come together around projects they believe in and want to make happen. Livability Lab projects specifically do not require total community buy-in; the goal is a variety of different projects, each attracting its own particular adherents/activists.

Many Livability Lab projects have turned into sustainable organizations, and community members are now answering the HOW question for themselves. To find out more, join the community at Livability Lab 4.0 100-Day Challenge Celebration this February 6, online or in-person (8.30 am to noon ET). The Muskegon community will be celebrating not just its increased agency, but also specific projects including transportation to work, access to child care, youth engagement, reducing gun violence, racial disparity in maternal/child health, and many more!

UPPER RIGHT: YOU DECIDE IT ALL

In this corner sit our Wellville 5 communities. The Wellville National team’s engagement with them focuses on questions: What do you want to do? And how? We ask what community members would like to achieve, what they’d like to fix or change, and then we ask how they could do that. (A psychologist would talk about intrinsic motivation here: You are doing what you want rather than responding to some external incentive.)

Questions we have asked over time include:

What could you do to scale? With whom could you partner to do so? Is there some complementary organization to whom you could outsource? Is there some other local organization to share a storefront with? What is the long-term impact? Would you like to talk with someone from another Wellville community (or elsewhere) who is addressing the same problem you are? What really needs fixing here? And what caused the problem in the first place? It’s probably not the current situation; it’s what led to it. Why are people not showing up? Is it that they don’t care, or lack transportation or child care, or just inconvenience? (In one of its few silver linings, COVID showed that convenience can help increase attendance at meetings.)

Now for the big question: Who decides where to sit on the chart? The chart shows who decides the details of a project …. but at the beginning, either “you” or “they” have the right and power to agree or reject the deal in the first place. The problems arise when the terms of the deal are unclear: So often, it’s a case of “We thought you were giving this to us… but we missed the terms and conditions!”

We hope this chart helps you understand what you as a community are signing up for while you still have the power to say no to terms you might regret.