Learning from Communities on the Way to Wellville

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) Building is a century-old, 109,303-square-foot neoclassical structure. It sits with “a sense of gravity and permanence”: a marble-walled box in the neatly squared grid of Washington, D.C. streets and avenues. Located alongside the National Mall, in view of the Lincoln Memorial, on the ancestral lands of the Anacostan people, the NAS is dedicated to our nation’s faith in science as the investigation of truth.

Last year, as the early bloom of cherry blossoms shook off the last days of D.C. winter, a group I was part of gathered inside the NAS building for the kind of shared truth-telling that can either clarify or complicate (and sometimes both) our efforts to solve the most difficult challenges we face. The occasion – a symposium called “Shifting the Nation’s Health Investments to Support Long, Healthy Lives for All” – brought together a range of experts: health care executives and academics, lawyers and legislators, physicians and philanthropists. We were there to take stock of the nation’s lack of progress over the decade since the publication of two milestone reports (here and here) that highlighted “the paradoxical combination” of “great wealth and high spending on health care” in the U.S. with our “relatively poor health status and lower life expectancy” compared to peer countries.

Asking Better Questions

Wellville, the national nonprofit I lead, is often invited to meetings like these. So I was there, sharing what we’re learning through our own 10-year project, which supports diverse groups of stakeholders as they work together to improve health in five U.S. communities: Clatsop County, OR; Lake County, CA; Muskegon County, MI; North Hartford, CT; and Spartanburg, SC.

People in our Wellville communities are learning that if we want better results, we need to ask better questions: What future do we want? What’s holding us back? And what will it take to get there? The magic happens when we listen to each other across neighborhoods and institutions, in widening circles that expand our perspective, our sense of connection, and our collective capacity for change. The only way to get unstuck is to get outside our silos and our certainty, to see some new path forward together that none of us saw on our own. It’s like that quote attributed to Albert Einstein: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

Last year’s NAS symposium was a moment calling for this kind of reflection. The decade-old reports were filled with recommended policies and investments needed to improve our nation’s health. However, in his remarks, Victor Dzau, MD, President of the National Academy of Medicine, observed: “So here we are 10 years later and we continue to face these familiar problems. Americans are actually living three years less on average than in 2019… (and) longstanding problems of poverty, discrimination, racism, and access to care are continuing.”

Over two days of discussion, symposium participants were frustrated: “These are the intended outcomes of the systems we’ve designed.” They were also resolute: “If we don’t want to have the same conversation in 10 years, we need to change course.”

Indeed, there were some signs of hope. A few of us suggested learning from folks “on the ground,” like those working for change in our Wellville communities. Maybe the real work of a room full of national experts is to ask who is not in the room. What truths emerge when we invite more people and perspectives to think outside the building (box) together?

That’s a question that the guy sitting nearby – gazing thoughtfully under the shade of elm and holly trees – might appreciate. On the southwest corner of the NAS grounds is a statue of Einstein, four tons of bronze, 12-feet high and resting peacefully on a circular bench that forms a magnificent memorial engraved with another one of his quotes:

“The right to search for truth

implies also a duty;

one must not conceal

any part

of what one has recognized

to be true.”

What Future Do We Want?

Like most of us, the people at last year’s NAS symposium and the people in our Wellville communities want the same thing: a future where our kids, our families, our neighbors and our neighborhoods thrive. But even when the vision is clear, the way forward can take a little more digging.

While every community has its strengths and challenges, looking below the surface can reveal patterns (truths) we might miss otherwise. For instance, although the Wellville community of North Hartford, CT, is located in the nation’s fourth “healthiest” state, its residents experience vast disparities in life expectancy, chronic illness and the underlying social, economic and environmental conditions needed for wellbeing. Whether we view these disparities as individual failings or manifestations of larger societal problems might depend on how deep we’re willing to dig.

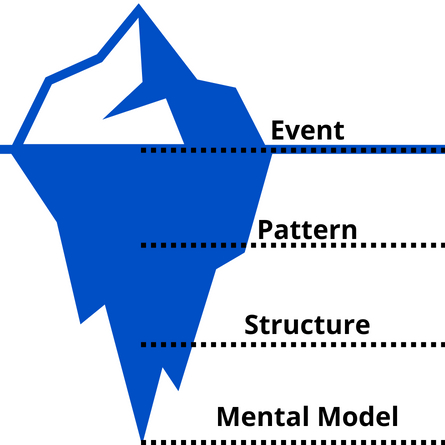

The iceberg model is a handy way of understanding how the results (“events”) we see – like healthy or unhealthy communities – emerge from complex relationships among organizations, policies and norms (“structures”), which are shaped by the ideas and assumptions we hold (“mental models”). Consider the vast network of social, economic, legal and political systems involved in producing that cup of coffee you enjoyed this morning. Looking below the surface gives us a more complete view of what’s going on. It can get pretty messy pretty quickly.

As Dr. Dzau noted, the problem of deteriorating and inequitably distributed health is not isolated from other problems. In this moment, we face urgent and intertwined threats from a range of “long-standing, ever-appalling underlying injustices: the climate crisis, economic inequality, endemic military conflict, the coronavirus pandemic, police brutality, systemic racism, and more,” according to the On Bridging report by community organizer Rachel Heydemann and john a. powell, founding director of the Othering & Belonging Institute.

These often-grim headlines are a call to action. They unsettle our sense of who we are. Bad news comes at us with a frequency and fury that makes it easy to assume human beings are selfish by nature, rather than the more radical – and more accurate, based on evidence from the last 200,000 years – view that we are a caring, compassionate and cooperative species: “Most people, deep down, are pretty decent,” says historian Rutger Bregman.

So, if most people are pretty decent, how did we get ourselves into this jam — and how do we get out? “Without question, the external systems and structures of our world need to be examined and adjusted,” writes Wendy Hasenkamp, PhD, neuroscientist and Science Director, Mind & Life Institute. “Yet a more hidden source of our current problems runs so deep that it is often overlooked. The very mindset that has enabled today’s crises lies inside of us.”

If it’s transformation we want, we’ll need to move from the tip to the base of the iceberg, where the thinking that informs our actions that lead to our outcomes takes shape. Seeing our role in the problems we face is not about blame, but belief in our collective power to create the changes we want:

- On poverty, sociologist Matthew Desmond offers a path forward: “We don’t need new solutions to this problem as much as a new mind-set, a renewed national commitment to broad prosperity.”

- On climate change, research by professor Christine Wamsler and Jamie Bristow, co-director of The Mindfulness Initiative, concludes: “The mind itself is increasingly understood as a root cause of climate change and a barrier for action-taking.” This mindset can shift if we “make it visible.”

- And on racial bias in the criminal justice system, professor Rhonda Magee, JD, advises us to combine “teaching and learning about race…with regular experiential practices for opening awareness” to help us work more effectively “in increasingly diverse and conflict-laden environments.”

We can get to a future where everyone thrives together. It starts by understanding the thinking that got us to the present.

What’s Holding Us Back?

In 2019, with prodding from our Advisory Board, Wellville dug a little deeper into what we were learning with our five communities and what, fundamentally, seemed to be standing in the way of equitable wellbeing. We diagnosed a central problem: America’s deteriorating health and growing inequities result from short-term self interest.

Thinking and acting according to short-term self interest is encouraged and perpetuated by systems, structures, culture and beliefs that too often favor the individual over the collective, the immediate over the future.

We don’t have to look far for examples where this can produce a vicious cycle:

- Our nation’s health care system costs us $4.5 trillion per year or $13,493 per person (2022), mostly for treating illnesses we could have prevented through long-term investments to keep communities and people well in the first place.

- A fixation on election cycles and quarterly earnings means that candidates and corporations prefer quick wins that benefit their most influential stakeholders.

- Buying on Amazon might be faster and cheaper for individuals, but harmful to local economies and human connection on the whole.

- The relentless pursuit of “likes” (and the last word) on social media has shortened our attention spans and made us more anxious, isolated and lonely.

- And affective polarization (when we feel strong positive emotions for our in-group and strong negative emotions for out-groups) has increased to such a degree that the most commonly cited quality Americans use to describe our country is “divided.”

Extreme self interest is especially harmful when it’s unexamined and embedded in our society. Again, Dr. Hasenkamp: Our belief that “we are separate from each other is so entrenched that we rarely see it, let alone question it. And it sets up a subtle, but very real sense of ‘self’ and ‘other’—a division that becomes woven into the systems we’ve created, which then serve to blindly reinforce and perpetuate it. This sense of separateness, when mixed with power, can result in tribalism, racism, all forms of othering, extraction of natural resources for profit, and exploitation of living beings and the land.”

But this is not inevitable.

So much of human history has been determined by just that – the stories we tell about the world and our place in it. As Sapiens author Yuval Noah Harari puts it, “Stories are the greatest human invention. People need stories in order to cooperate. But there’s also something else very important: they can change the way they cooperate by changing the stories they believe.”

More important than mindset is our awareness of mind-setting, our human capacity to see our own thinking and the actions and outcomes that flow from it. If we can think critically about the underlying assumptions, beliefs and values that hold our current systems in place, we can also think together about how we wish to remake our systems – and our world – anew.

Seeing and freeing ourselves from the habits of mind that no longer serve us is a process. As noted in this report by FrameWorks: “Mindsets…are highly durable with deep historical roots. They emerge from and are tied to social practices and institutions that are woven into the very fabric of society. As such, they tend to change slowly.” However, when events cause us to redefine “how we think about fundamental aspects of our society like health and race,” mindset shifts can speed up.

It doesn’t happen in isolation. The only way to see what we don’t see is together. We need each other to transform.

What Will It Take to Get There?

Lake County is a sprawling rural northern California community with just under 68,000 people across 1,329 square miles. It is a great distance and a great contrast in landscape from orderly D.C. It is also a place of deep time: 68-square-mile Clear Lake in the center of the county is the oldest lake in North America and the Mount Konocti volcano on its south shore last erupted 350,000 years ago. The first people arrived in Lake County over 10,000 years ago, if you believe Wikipedia – or 22,000 years ago according to members of the local Pomo tribes, who generously shared their stories with people from our five Wellville communities when we gathered on their land in May 2022. Arriving now under those western skies unconstrains our belief in what’s possible, sometimes by unconcealing the path we took to get here.

The occasion was the 2022 Wellville Gathering, our annual three-day convening that brings together community changemakers (residents and organization folks) from the five places participating in the 10-year Wellville project. The annual Gatherings, which are hosted in one of the Wellville 5 communities each year, are an opportunity to set aside daily distractions, get to know each other more deeply, and reflect together in ways that reveal bottom-of-the-iceberg truths hiding in our assumptions. The Lake County-hosted Gathering began with members of the Pomo tribes sharing their truths – about the historical and continued trauma inflicted on their people – and inviting us all to begin to heal together.

It was an opening that carried into the Wellville community team huddles:

- During Spartanburg, SC’s huddle, the mayor and assistant city manager listened as members of Spartanburg Initiative for Racial Equity Now (SIREN) advocated for a shift in how community development decisions are made, proposing a more central role for residents of the primarily Black neighborhoods that were decimated by urban renewal.

- Clatsop County, OR team members strategized on ways to elevate the voices and priorities of the Hispanic population.

- North Hartford, CT residents and organization leaders shared their stories of self, us and now, deepening their relationships and resolve to bring a grocery store to an area of the city that has been deemed a food desert and a food swamp.

- An experienced group of changemakers from Muskegon County, MI explored ways to support the next generation of leaders in creating the changes they want to see.

- And the Lake County team mapped out a community engagement process, including more intentional outreach to Native Americans, to create a shared plan for county-wide health improvement.

Gathering in this way creates a particular kind of togethering that can generate profound change in ourselves, our institutions and our communities. We expand our perspectives: “It’s valuable to explore outside of my own little bubble, get more involved in other organizations’ initiatives, and see how we can align for bigger impact,” shares a participant from Muskegon. And we reconnect with what’s most important: “This experience has literally been life changing for me both personally and professionally,” adds Debi Martin, Program Officer at LISC Connecticut, who grew up in the Upper Albany neighborhood of North Hartford. “Participating in Wellville and connecting with the people I’ve met along the way, especially at the Gathering in Lake County, is helping me find my voice again – and helping me to remember and to learn from all the reasons I lost it in the first place.”

At a community level, building relationships, bridging differences and finding our commonality can mend tears in the social fabric that have left so many more of us feeling alone. “The intervention for othering is not same-ing, but belonging,” writes professor john a. powell. “Belonging is based on the recognition of our full humanity without having to become something different or pretend we’re all the same… Belonging requires both agency and power to cocreate.”

There’s no template for this work. How communities come together depends a lot on local people and context. When we started working with the Wellville 5 communities in 2015, we didn’t hand them a destination and turn-by-turn directions. Having the power to shape the kind of community you want to live in improves health in ways that prescriptive interventions can’t.

Communities need to walk their own path. But sometimes it helps to have a catalyst. Wellville plays its part by providing dedicated advisors who collaborate with the people who live and work in our communities. During the 10-year Wellville project, we’ve helped our communities convene stakeholders across neighborhoods, institutions and systems to:

- Listen empathetically and generatively;

- Reveal ground truths about the causes of harm and health;

- Imagine new futures; and

- Move forward together, learning and adjusting through all the messiness, breakdowns and potential opportunities that emerge along the way. (As Wellville founder Esther Dyson includes at the end of every email she sends: “Always make new mistakes!”)

This approach has produced a range of community-led actions in the Wellville 5, with long-term shared investments and shared benefits in areas such as early childhood, paths out of homelessness, diabetes prevention, food access and equity and inclusion.

Doing this work together and then telling stories about it can be transformative for tellers and listeners. By sharing these stories more broadly, “Wellville is contributing to a new narrative about communities thriving through long-term shared interest,” says Wellville Advisory Board member Tony Iton, MD, JD, MPH, Senior Vice President at The California Endowment.

Seeking Truth Together

Shifting our nation’s health will take more than five places. It turns out there are a growing number of multi-site initiatives – like BUILD Health Challenge, Invest Health, Purpose Built Communities and Wellville – with hundreds of communities and partners pointing the way to more effective, more equitable and more sustainable approaches to health and wellbeing. What could we accomplish together that none of us could accomplish on our own?

We can connect rooms full of national experts with rooms full of community folks to dig deep, learn together and cultivate new ways of thinking that create virtuous cycles of thriving together. Redesigning from the base of the iceberg is in our long-term shared interest.

Some areas to start:

- Approach: National organizations, like the ones represented at last year’s NAS symposium, can provide valuable perspectives and resources to communities. But we need to do so in harmony with local people, cultures and context. Do we show up as experts eager to implement our evidence-based models? Or are we more open and curious? It takes a patient and enduring presence to navigate the uncertainties of co-development and learning as we go.

- Connections: Networking within and across communities can help us spread ideas and accelerate progress. We can also convene in ways that deepen our sense of shared purpose, interdependence and belonging. Who else needs to be part of this work? What does it take to see past our assumptions about each other? How can relationship-building move from transactional to transformational?

- Learning: Cross-community research could reveal important insights, while putting data and power in the hands of local changemakers. What should be measured and who gets to decide? How can continuous learning on the ground inform the larger system? How can moving from a prescriptive strategy to an emergent one expand agency and ownership, and potentially create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts?

- Narrative: Our field recognizes the importance of narrative in shaping how we see the problems we face – and how we generate the public and political will to address them. How can we contribute to a national narrative shift by weaving together stories of communities? How can we work with national funders and influencers to elevate these stories? And what can we learn from cognitive and contemplative sciences about the power of changing our minds?

- Context: Communities are situated in larger political and social contexts that can enable or restrict their ability to make the changes they want. How can we work collectively to shift state and national policies, systems and structures so that they support community-driven health and wellbeing? How can community development advance local priorities while engaging a broader range of assets and allies?

- Investment: The value of community collaboration goes beyond the specific programs and services they produce. So should the funding. How can we mobilize the resources needed for local teams to continue to lead and sustain this work? And how can we co-invest in shared solutions to shared priorities?

Our collective wellbeing depends on healthy, connected communities where everyone belongs, everyone matters and everyone can contribute to our common good. We need the full diversity of our perspectives and lived experiences to see larger truths. We need to connect across differences (real and perceived) that too often keep us apart. We need each other to get unstuck from the systems that constrain us.

We need each other to create the world anew.

The investigation of truth is in one way hard and in another way easy. An indication of this is found in the fact that no one is able to attain the truth entirely, while on the other hand no one fails entirely, but everyone says something true about the nature of things, and by the union of all a considerable amount is amassed.

Translated excerpt from Aristotle’s Metaphysics, inscribed on the façade of the National Academy of Sciences Building